Cannnes film festival never disappoints with lineup of movies felt like a call to pay attention in a world in turmoil. This year even before the festival’s midway point, it was clear that this year’s Cannes, with films from all over the globe, was positioning itself as a festival for a world teetering on the brink. No matter where they hail from, filmmakers are telling stories about people on the verge of revolution — or an apocalypse festival opened on Tuesday with a zombie apocalypse: The Dead Don’t Die, Jim Jarmusch’s gently scathing tragicomedy set in small-town America -it’s fizzy and fun, with an undertow of despair: an apocalyptic zombie comedy in which an excess of polar fracking has warped the planet’s rotation and reanimated the corpses at the local morgue.

Cannnes film festival never disappoints with lineup of movies felt like a call to pay attention in a world in turmoil. This year even before the festival’s midway point, it was clear that this year’s Cannes, with films from all over the globe, was positioning itself as a festival for a world teetering on the brink. No matter where they hail from, filmmakers are telling stories about people on the verge of revolution — or an apocalypse festival opened on Tuesday with a zombie apocalypse: The Dead Don’t Die, Jim Jarmusch’s gently scathing tragicomedy set in small-town America -it’s fizzy and fun, with an undertow of despair: an apocalyptic zombie comedy in which an excess of polar fracking has warped the planet’s rotation and reanimated the corpses at the local morgue.

Driver and Bill Murray play the droll small-town cops attempting to clean up the mess, while an undead Iggy Pop lurches off to the diner in search of fresh coffee. What does it matter if Jarmusch’s approach to this material is, finally, too laidback The Dead Don’t Die styles itself loosely – too loosely – as a Trumpian satire, offering a jaundiced sketch of the brain-dead red states and casting Steve Buscemi as a dirt farmer whose baseball cap bears the garbled logo “Keep America White Again”. But the film might just as easily stand as a joke about Cannes… as for the most part, the characters in The Dead Don’t Die aren’t particularly powerful or vulnerable or bad or angry, and they live comfortably enough. They’re just tired, and ready for the end to come….

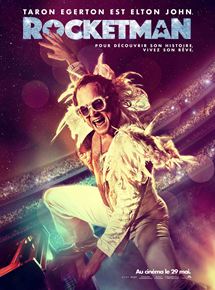

Dexter Fletcher’s rousingly good natured Rocketman is the authorised-version movie about the legendary singer-songwriter Elton John: written by Lee Hall, produced by David Furnish and exec produced by the man himself. It’s following or living up to Elton John’s sensational songs, the masterpieces which each seem like mini-movies in themselves – or at the very least the euphoric accompaniment to the most moving final montage you’ve ever seen. But sometimes the songs are part of a fantasy sequence, choreographed in such an interesting way.

Dexter Fletcher’s rousingly good natured Rocketman is the authorised-version movie about the legendary singer-songwriter Elton John: written by Lee Hall, produced by David Furnish and exec produced by the man himself. It’s following or living up to Elton John’s sensational songs, the masterpieces which each seem like mini-movies in themselves – or at the very least the euphoric accompaniment to the most moving final montage you’ve ever seen. But sometimes the songs are part of a fantasy sequence, choreographed in such an interesting way.

As Elton John, Taron Egerton gamely does a middleweight impersonation, more comfortable with the lighter side: better at the tiaras than the tantrums. The story takes us from the world of Reg Dwight, a bright, shy kid in Pinner, living with his mum (Bryce Dallas Howard) and emotionally stilted dad (Steven Mackintosh) who without knowing it is sowing the seeds of creative pain and rage. There’s also his adoring gran (Gemma Jones) who encourages his music. and finally his devastatingly handsome lover and manager John Reid (a toxically sexy Richard Madden) with whom he falls out horribly. It skates us through the glory days of the 70s, the astronomic record-sales, the coke and booze, the misjudged straight marriage and perhaps equally misjudged purchase of Watford FC, concluding with rehab and a 12-step meeting from which the movie is recounted in piously conceived flashback.

As Elton John, Taron Egerton gamely does a middleweight impersonation, more comfortable with the lighter side: better at the tiaras than the tantrums. The story takes us from the world of Reg Dwight, a bright, shy kid in Pinner, living with his mum (Bryce Dallas Howard) and emotionally stilted dad (Steven Mackintosh) who without knowing it is sowing the seeds of creative pain and rage. There’s also his adoring gran (Gemma Jones) who encourages his music. and finally his devastatingly handsome lover and manager John Reid (a toxically sexy Richard Madden) with whom he falls out horribly. It skates us through the glory days of the 70s, the astronomic record-sales, the coke and booze, the misjudged straight marriage and perhaps equally misjudged purchase of Watford FC, concluding with rehab and a 12-step meeting from which the movie is recounted in piously conceived flashback.

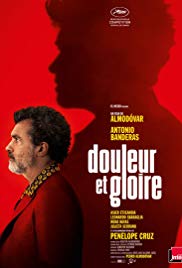

In “Pain and Glory,” it is frequent collaborator Antonio Banderaswho rocks that coif, which instantly signals to audiences that the tormented filmmaker he plays was inspired, at least in part, by the man who launched his career with “Labyrinth of Passion” and “Law of Desire” more than three decades earlier. Both the character and his creator have mellowed in that time, during which Spanish society has relaxed its stance toward the

In “Pain and Glory,” it is frequent collaborator Antonio Banderaswho rocks that coif, which instantly signals to audiences that the tormented filmmaker he plays was inspired, at least in part, by the man who launched his career with “Labyrinth of Passion” and “Law of Desire” more than three decades earlier. Both the character and his creator have mellowed in that time, during which Spanish society has relaxed its stance toward the

counterculture to which he gave voice.

Pedro Almodóvar directs Antonio Banderas in this remarkably mature metafiction, exploring the emotional scars that underly his own physical frailty Pain and Glory is self-indulgent, as these films tend to be. But if Almodóvar gets away with it, it isn’t because he has built his memories and musings into a grand Fellini-esque statement on life and art, it’s because he has done the opposite, and fashioned a charmingly modest collection of murmured conversations and reflections. Might the handyman have a fling with the boy’s vivacious, neglected mother (who else but Penélope Cruz), or even with the boy himself? Nope: the flashback culminates in Salvador glimpsing the handyman’s statuesque naked body. But unless you view Pain and Glory through a filter of deep affection for Almodóvar, you will see it as minor work: not painful, but not glorious, either….

Pedro Almodóvar directs Antonio Banderas in this remarkably mature metafiction, exploring the emotional scars that underly his own physical frailty Pain and Glory is self-indulgent, as these films tend to be. But if Almodóvar gets away with it, it isn’t because he has built his memories and musings into a grand Fellini-esque statement on life and art, it’s because he has done the opposite, and fashioned a charmingly modest collection of murmured conversations and reflections. Might the handyman have a fling with the boy’s vivacious, neglected mother (who else but Penélope Cruz), or even with the boy himself? Nope: the flashback culminates in Salvador glimpsing the handyman’s statuesque naked body. But unless you view Pain and Glory through a filter of deep affection for Almodóvar, you will see it as minor work: not painful, but not glorious, either….

So it’s on with the show; the films are piling up all around. Having won the 2016 Palme d’Or for I, Daniel Blake, Ken Loach returns to the fray with Sorry We Missed You, spotlighting a zero-hours Britain where exploitation passes itself off as freedom. Kris Hitchen gives a full-blooded performance as Ricky, a Mancunian delivery man racing the clock and chasing the dream like a modern-day Tom Joad. But his debts are mounting, his family is in freefall and he’s struggling not to fall asleep at the wheel.

So it’s on with the show; the films are piling up all around. Having won the 2016 Palme d’Or for I, Daniel Blake, Ken Loach returns to the fray with Sorry We Missed You, spotlighting a zero-hours Britain where exploitation passes itself off as freedom. Kris Hitchen gives a full-blooded performance as Ricky, a Mancunian delivery man racing the clock and chasing the dream like a modern-day Tom Joad. But his debts are mounting, his family is in freefall and he’s struggling not to fall asleep at the wheel.

Cannes, the sense that we’re aboard a luxury ocean liner, toiling through choppy waters, to the point where it has almost become the festival’s natural state. It’s buffeted by changes in the industry at large (steadfastly holding out against the dominance of Netflix ). It’s flayed by criticism of its dearth of female talent (this year’s competition finds room for a record-equalling four women directors, though you’d struggle to pick them out amid the 19 men). And all the while, Cannes stays upright and doggedly cleaves to its course.

Cannes, the sense that we’re aboard a luxury ocean liner, toiling through choppy waters, to the point where it has almost become the festival’s natural state. It’s buffeted by changes in the industry at large (steadfastly holding out against the dominance of Netflix ). It’s flayed by criticism of its dearth of female talent (this year’s competition finds room for a record-equalling four women directors, though you’d struggle to pick them out amid the 19 men). And all the while, Cannes stays upright and doggedly cleaves to its course.

Website : http://www.festival-cannes.com